To foster Bonds Between the Holy Land and the world

Pro Terra Sancta is a non-profit organization that works in the Holy Land to support the Custody of the Holy Land in its mission of preserving the Holy Places and supporting the Christian communities in the Middle East.

Projects

Education and Assistance, Humanitarian Emergency, Conservation and Development are the pillars of our projects

in the Holy Land.

Discover the projects

Campaigns

With our campaigns we support fundamental projects for the reconstruction and support of places and

people.

Discover the campaigns

Itineraries

Pro Terra Sancta organizes numerous experiential trips to the Holy Land to discover something great

artistic, historical and spiritual heritage.

Discover the itineraries

JOIN US

Receive news and stories from the Holy Land

Discover our projects in advance, field testimonies, and exclusive content dedicated to those who want to stay close to the Holy Land.

Our interventions

Discover our interventions on the territory

Discover our interventions on the territory

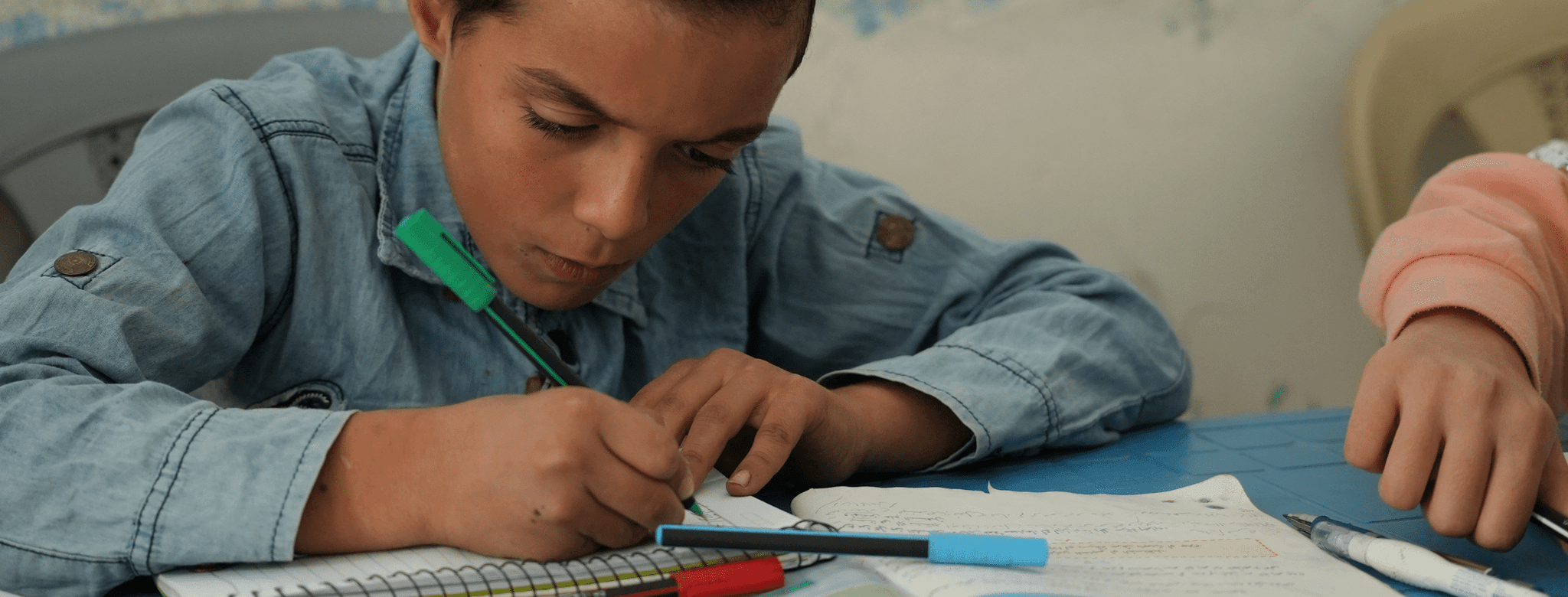

Education and training

Conservation and development

Emergency aid

Socio-entrepreneurial activities

Syria/Damascus – Support for local educational works

Assistance to families in difficulty at the emergency center set up in the Franciscan convent of Bab Touma in Damascus.

Lebanon – Support for local educational works

Lebanon is a country devastated by conflict and an unprecedented economic and social crisis , where most of the economic availability comes from the contribution of the Lebanese who left the country in the diaspora and now live elsewhere. In this difficult context, Pro Terra Sancta is active on several fronts to help this tormented […]

The Dar Al-Majus Bazaar

“Majus” in Arabic means “Magi”, and “Dar” is the translation of “house”; therefore the bazaar is “the house of the Magi“, the place where local artisans build gifts full of meaning and value. Since 2022, the Dar Al-Majus bazaar has been active in Bethlehem at the Dar Al-Majus Community Home, a fair trade project that […]

Donating is an act of love

With your gesture, you provide real help to those living in situations of emergency and poverty.

Support cultural, educational, and training activities

$ 50

Help us preserve the holy land sanctuaries

$ 80

Help us support needy families and children

$ 100

Secure Payment

Secure Payment

Donate Now

Donate Now

Friend Sites

Receive news and stories from the Holy Land